Somewhere between my inbox and the fluorescent lights of a corporate boardroom, my book died. Not with a dramatic “no,” just with that gentle industry bullet: “We don’t feel this project is viable in the current market.” The longer you stare at that sentence, the more it stops sounding like feedback and starts looking like a map—one that doesn’t trace readers’ desires so much as the power lines of five companies that decide which stories are allowed to exist.[1]

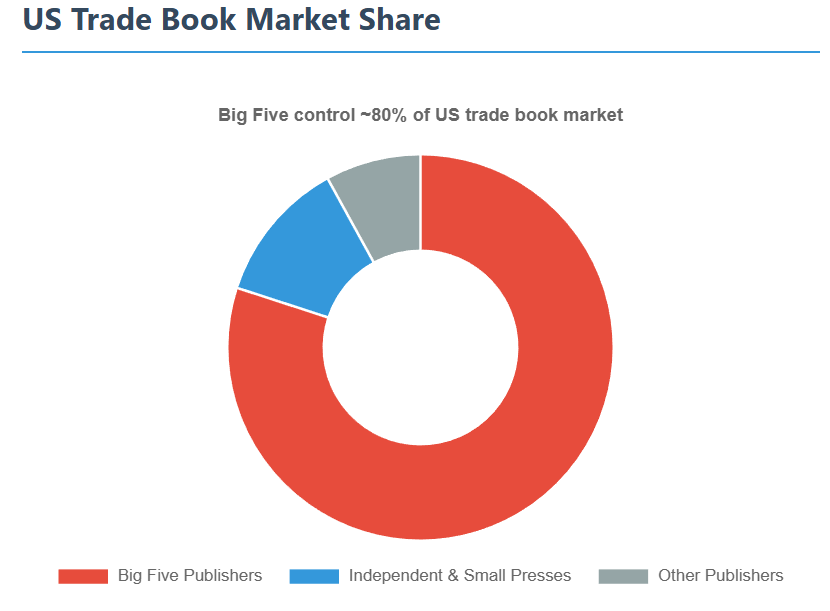

Those five power lines should be familiar to anyone who’s tried to publish a book: Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, Hachette, and Macmillan. In the U.S. trade market, they are sometimes said to control upwards of 80% of the space where most general‑audience books live. Globally, they sit at the top of an industry worth well over 100 billion dollars, their parent corporations appearing in rankings of the world’s largest publishers with revenues in the billions.[2]

When an editor tells a writer, “The market isn’t there,” what they often mean is that these five structures do not see a profitable place for that book on their internal spreadsheets this quarter. That is not the same thing as saying that no readers would care.[3]

My book versus the five doors

I wrote a messy book.

It was full of night‑shift workers, migrants, cleaners—the people who usually appear in novels just long enough to hand the main character a drink, a lesson, or a warning. It didn’t fit neatly into “romance” or “crime” or “upmarket book‑club fiction.” It just tried to tell the truth as it appeared on buses at 1 a.m., in share‑houses and cash‑in‑hand jobs, in the quiet violence of being invisible.

Agents called it “powerful,” then “a difficult sell.” Editors called it “exciting,” then “hard to position.” Position. As if a life needed better shelf placement.

What took time to grasp was that the book wasn’t only trying to survive readers’ tastes. It was trying to pass through five particular doors, each with its own agents, scouts, marketers, accountants, and risk models. These weren’t just publishers; they were the landlords of the mainstream imagination. If a book doesn’t pass through at least one of them, it starts life on the outskirts of town with a photocopied map and no streetlights.[4]

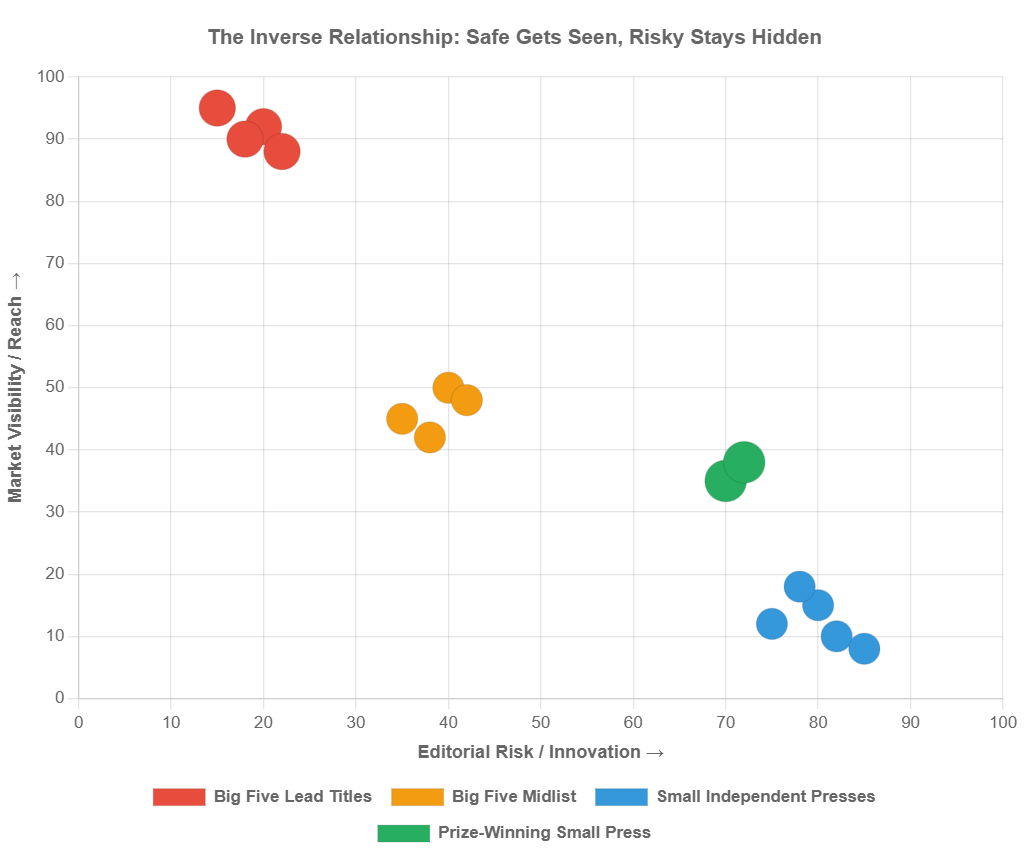

Inside those doors, my book didn’t compete in some pure arena of “all books ever written.” It competed against a carefully curated shortlist of titles the company had already decided to crown as this year’s chosen ones—the “lead titles,” the “big books” with big advances, big marketing budgets, and big, safe vibes. My story was not one of them. It never stood a chance to be.[5]

The crime scene in charts

To see why those doors feel so heavy, it helps to imagine two graphs drawn on a whiteboard in that bright boardroom where someone quietly decided my book did not “fit the list.”

Graph 1: The shrinking world

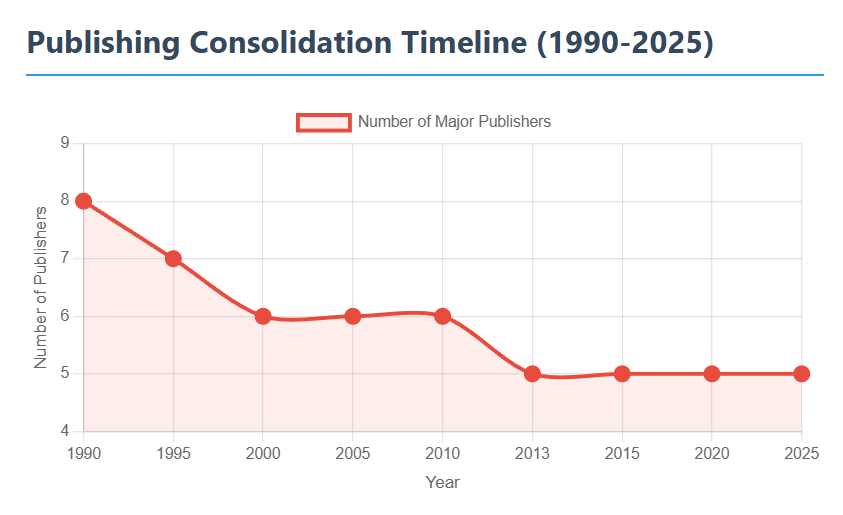

Picture a line chart from 1990 to 2025. In the early 1990s, the industry still talked about a “Big Six.” Over the next decades, mergers turned that six into five. The most symbolic moment came in 2013, when Penguin and Random House fused into a single giant, creating the largest trade publisher on Earth and formalising the phrase “Big Five.” Each merger shaved off another independent pole of power and folded its backlist into a smaller number of corporate hands.[6]

By the 2020s, that imagined graph shows five thick coloured lines dominating the page, while hundreds of thinner lines—smaller presses, family‑owned houses, niche imprints—fade into a grey fog underneath. The trend is not unique to books. Scholarly journal publishing, for instance, has seen similar consolidation, with the top five firms controlling well over half the market by the mid‑2020s. The lesson is simple: over time, the number of entities that can bring a book to mass market scale has steadily shrunk.[6]

Graph 2: The market share chokehold

Now picture a bar chart of the U.S. trade book market. On this chart:

The Big Five together are said to control more than 80% of the commercial trade space—hardcover and trade paperback fiction, nonfiction, children’s books—the territory that shapes what most people think “books” are.[7]

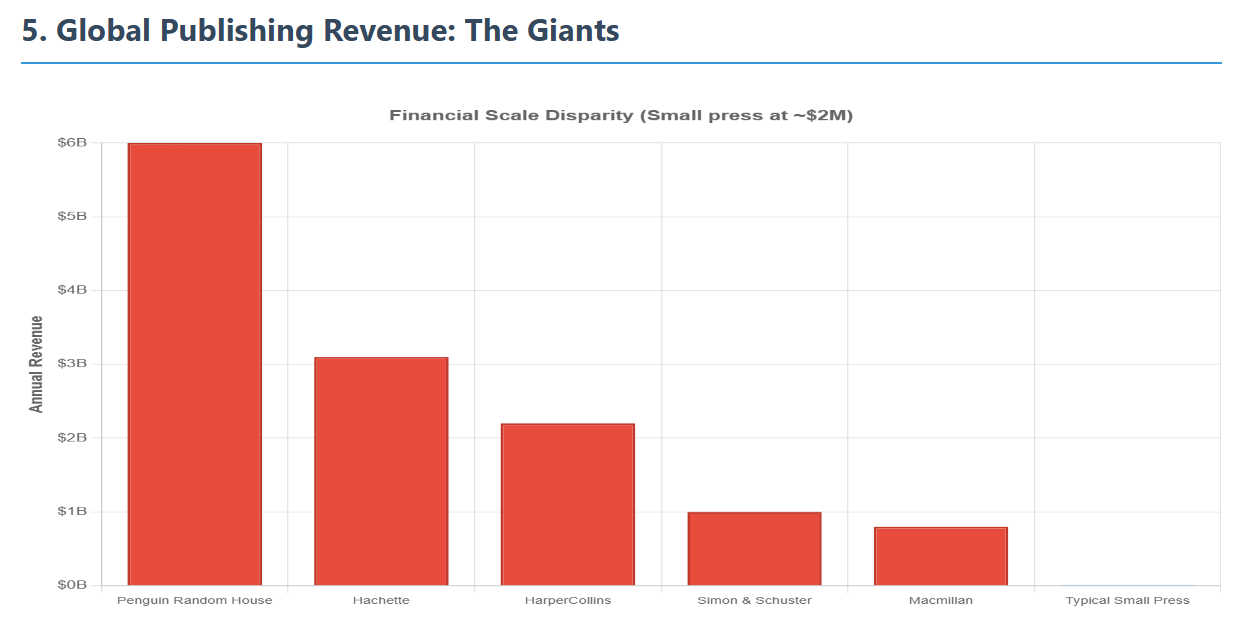

Globally, parent companies like Bertelsmann (which owns Penguin Random House) report annual publishing revenues around 6 billion USD, while Hachette and HarperCollins report multi‑billion‑dollar figures of their own.[2]

Even as digital formats, self‑publishing platforms, and mid‑size players grow, the Big Five continue to dominate bestseller lists and the all‑important hardcover and trade paperback categories where prestige is made.[1]

On that bar chart, the Big Five are five skyscrapers. Everyone else looks like the outline of a demolished building.

When people say, “The market didn’t want your book,” what they are often saying, whether they realise it or not, is, “These five skyscrapers didn’t see where you fit in their skyline.”[4]

The invisible filters (and how talent disappears)

The most effective kind of censorship doesn’t feel like censorship. It feels like “unfortunately” and “not quite right for our list.” It comes wrapped in compliments: “You’re so talented, but…”

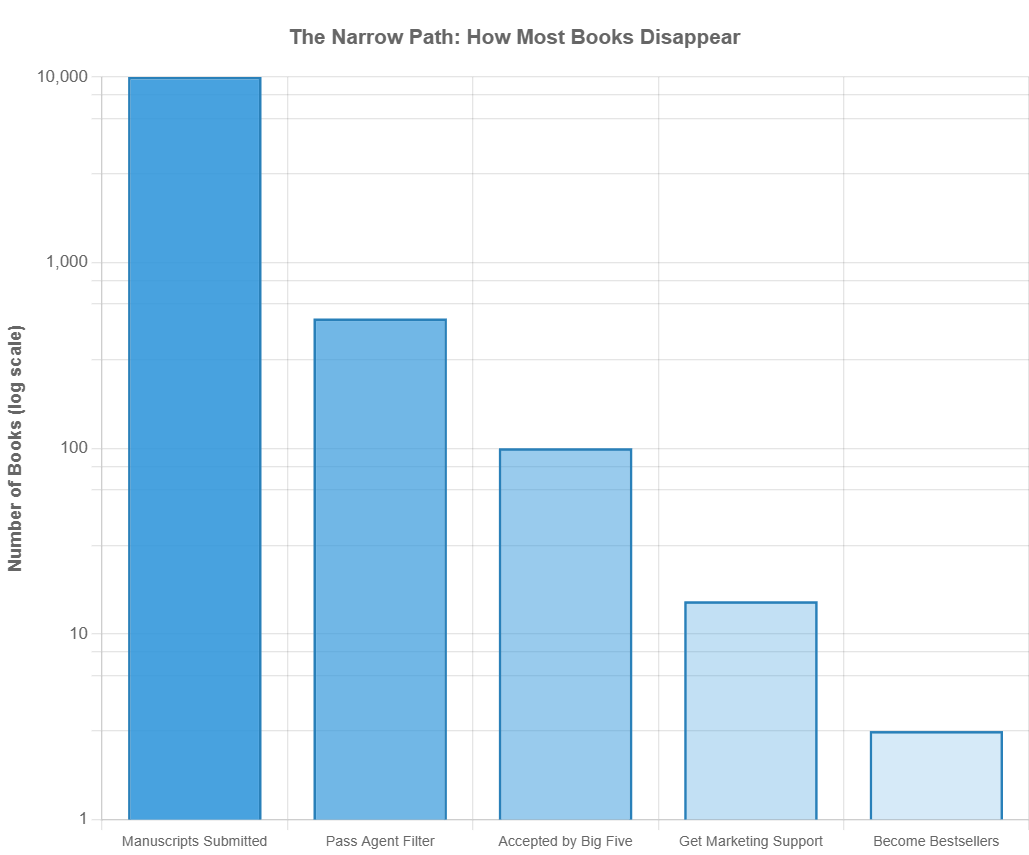

The modern publishing pipeline contains several filters long before a reader ever gets to decide:

Filter 1: Agents and acquisition

Most big houses will not read unsolicited manuscripts; you need an agent, and agents survive by placing books with those same Big Five doors. That instantly biases the pool toward projects that resemble things the Big Five have already bought.[8]

Query guidelines ask authors to pitch their work as “X meets Y”—”perfect for fans of Z”—because everyone is trying to read the tea leaves of past hits.[8]

Debut novelists are urged to write in easily marketable genres and to keep word counts within narrow bands, not because readers have taken a vote, but because gatekeepers fear stepping outside known lanes.[9]

If a manuscript does not echo a prior success, it is not just an artistic risk; it is a financial one. And risk is a dirty word inside a corporation answerable to quarterly earnings reports.

Filter 2: Marketing triage

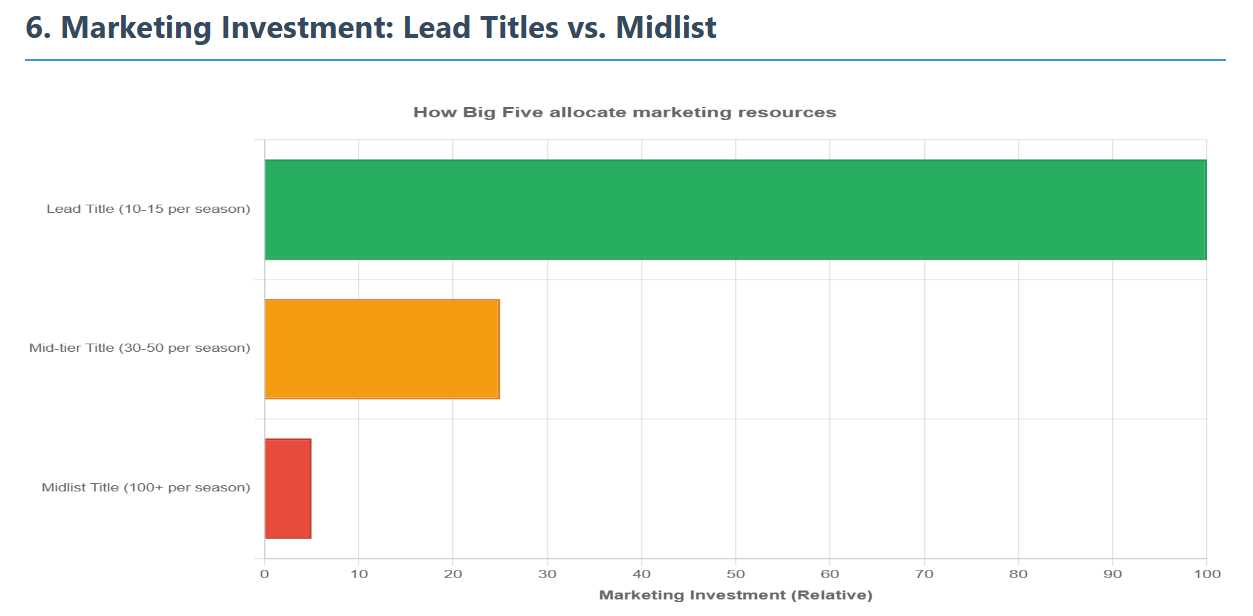

Inside a big house, not all “yes” decisions are equal. Only a fraction of books are designated “lead titles” and given serious marketing resources: publicists’ full attention, big advertising spends, widespread bookstore co‑op (the money that pays for front‑of‑store tables and window displays), festival pitches, media outreach.[5]

A Big Five marketing manager recently described lead‑title campaigns as the ones where creativity and budget flow freely, while lower‑priority books get formulaic treatment and minimal time.[5]

Lead titles are often by already‑famous authors or “big” debuts that internal teams have decided to bet on in a given season.[1]

The rest of the list—the midlist novels, quieter debuts, formally strange books—may be published with small print runs, little advertising, and almost no sustained publicity. When those books inevitably “underperform,” the industry treats that as proof that readers weren’t interested, rather than acknowledging that readers never really had a chance to find them.[10]

Filter 3: Coverage and distribution

National review outlets, chain bookstore buyers, festival programmers, and prize juries mostly orbit the largest companies and their publicists.[10]

Review editors must triage thousands of new books; they rely heavily on press releases, relationships, and the implicit signal of a big publisher’s push. A book that does not receive marketing dollars may never cross their desk.[10]

Chain retailers rely on co‑op money and sales reps, so the titles with paid placement are overwhelmingly from the Big Five or their major rivals.[4]

No attention becomes no sales; no sales become “evidence” that this kind of book doesn’t work. My manuscript didn’t smash into a single door. It quietly slid down these filters like water disappearing through a drain. On paper, that looks like an individual failure. On a graph, it is one more invisible point below the Big Five’s thick lines.

History’s little rebellions

Graphs, however, do not tell the whole story. Sometimes, books escape the default routes.

Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October began not with a Big Five powerhouse but with the U.S. Naval Institute Press, a small specialist publisher that took a chance on a dense, jargon‑heavy submarine thriller. Only after it became a surprise success did the big players move in.[3]

Christopher Paolini’s Eragon started as a self‑published fantasy novel, sold at fairs and school visits, before word of mouth made it too big for New York to ignore.[3]

William P. Young’s The Shack circulated in self‑published form among church communities, racking up sales that forced larger publishers to acknowledge its existence.[3]

If the system were particularly good at spotting talent or reader interest, these books would have been obvious “yes” decisions early on. Instead, they are remembered as charming outliers: stories that slipped past the filters and then had their success retrospectively claimed by the very machine that initially doubted them.

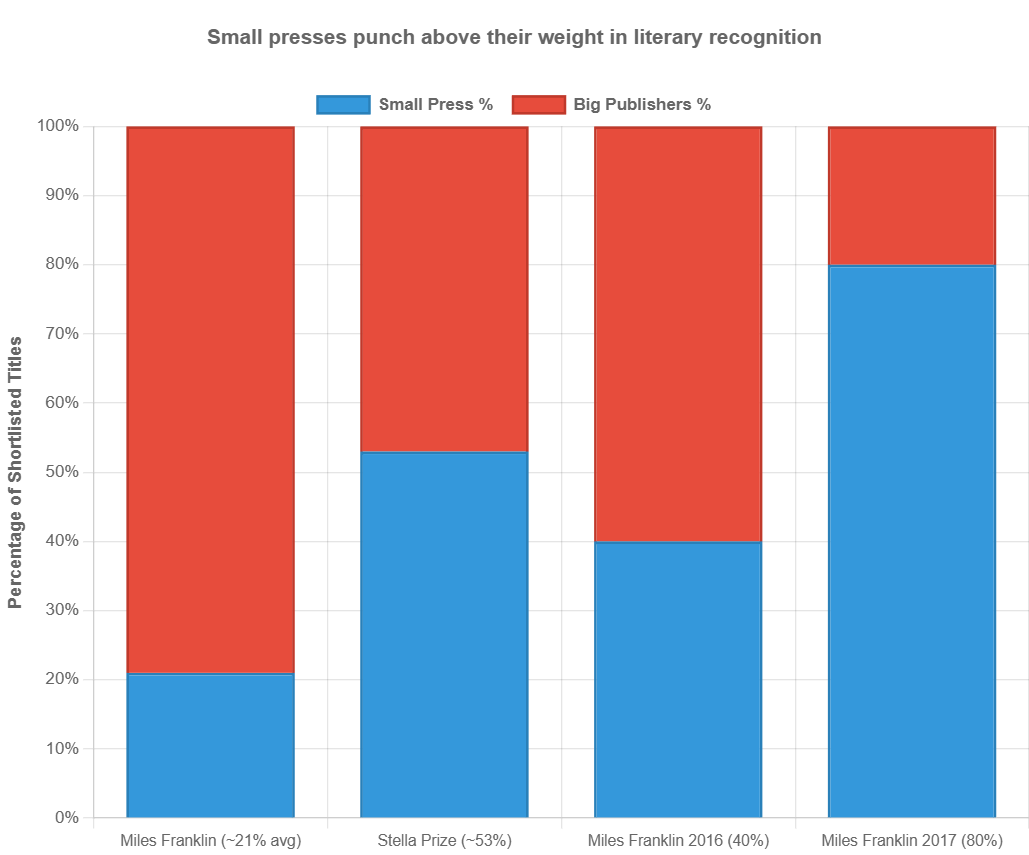

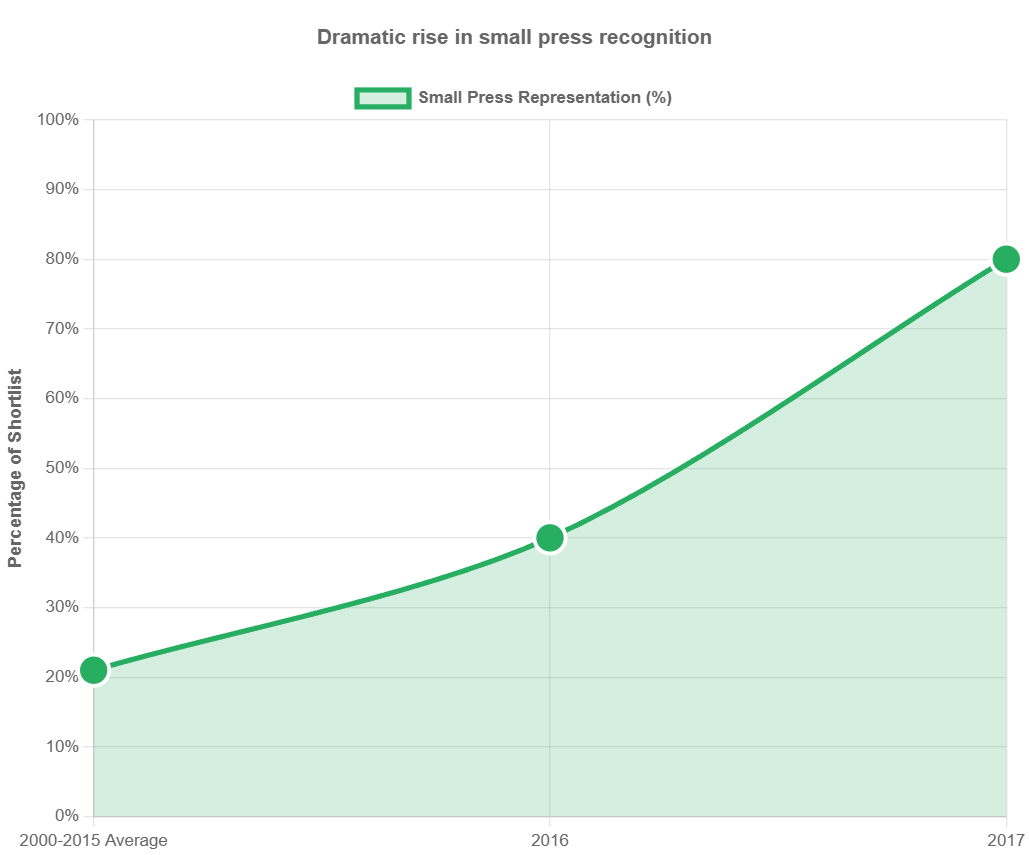

Zoom in on a different kind of chart—not sales, but prestige: literary prizes.

In Australia, small presses have had a striking presence in major awards. Data on the Miles Franklin and Prime Minister’s Literary Awards shows that while only around 21% of Miles Franklin shortlists since 2000 came from small presses, the proportion spiked to 40% in 2016 and 80% in 2017.[11]

The Stella Prize, focused on writing by women and non‑binary authors, has seen small publishers dominate even more. Of its early shortlists, 19 of 36 titles—roughly 53%—came from small presses, and half of the winners were published by independents like Text, Giramondo, and Affirm Press.[11]

Draw that graph and it looks like this: the Big Five (and their Australian equivalents) dominating sales bars, while small presses punch far above their weight in prize lists. The conclusion almost writes itself: the books considered most artistically significant or culturally urgent are often not the ones the biggest companies viewed as safest or most commercial.[11]

The bookstore, seen from the outside

Now return to the bookstore.

From the front door, it still looks like pure freedom: tables of bestsellers, “Most Anticipated” walls, staff‑pick shelves, front‑of‑store shrines to “The Book Everyone Is Talking About.” What you are really seeing is the visible tip of those earlier graphs—the intersection of market share, marketing budgets, and retailer economics—not the true range of written voices.[4]

Those face‑out, stacked‑high titles on tables and in windows? They are usually lead books from the biggest publishers, supported by co‑op money that pays for that real estate.[1]

The slim volume from a tiny press, if it is present at all, is probably spine‑out in a back corner, with one lonely copy wedged between beefier neighbours. On the sales graph, it is a hairline; in someone’s life, it might be the most accurate story they have ever read.[10]

My book never made it to those tables. But once it became clear that those shrines were not neutral reflections of “what readers want,” it became easier to walk past them and explore the unlit parts of the store. In those shelves, there were books that felt like cousins to mine: hybrid, angry, tender, “too niche,” “too quiet,” “too experimental.”

Many of them were published by small presses that survive on tiny margins, grant funding, volunteer labour, and sheer stubbornness. These publishers edit and design books at kitchen tables, run events in crowded bars and local libraries, and hope that one prize shortlisting might cross‑subsidise three loss‑making but necessary titles.[11]

If you drew a third graph—”risk vs. visibility”—the big five would cluster in the “lower risk, very high visibility” corner, while small presses would sit in “high risk, low visibility,” quietly producing some of the most daring work in the language.[10]

Where bestsellers really live

Here is the twist that keeps the writing going: a potential bestseller does not always start in those five towers. Sometimes it begins in a tiny office above a café, on a laptop in a share‑house, or in a spare bedroom with boxes of self‑published copies stacked against the wall. The mainstream often recognises it only after readers have already done the work.[12]

Recent shifts confirm that the skyscrapers are not invincible.

In the mid‑2020s, Sourcebooks, a once‑independent U.S. publisher, grew large enough in print units sold to be described as “cracking” the Big Five, effectively displacing one of them by volume in some measures.[12]

Audiobooks, BookTok‑driven backlist revivals, and niche digital communities have produced surprise hits that major publishers failed to predict, forcing them into reactive acquisition and reprint strategies rather than top‑down planning.[3]

When looking at those imagined graphs now, it helps not only to see the Big Five’s thick lines of market share but also the strange spikes that should not exist—surprise breakouts from independents, prize‑winning novels from micro‑presses, quiet books that become cult favourites years after release. Each spike is a little rebellion: proof that the machine does not know everything, that readers sometimes reach past what the algorithm and the front table tell them.[3]

For writers, this is both terrifying and liberating. Terrifying, because there is no guaranteed door. Liberating, because rejection from those five doors is not the same as a final verdict on a book’s worth. There are other routes:

Small presses that prioritise editorial risk over scale.

Regional and community publishers that reflect local realities more honestly than a global corporation ever could.

Self‑publishing and hybrid models, which shift some burden onto the author but also sidestep the first round of filters.[3]

None of these paths are easy. Most will not lead to a film deal or a seven‑figure advance. But if the goal is to put certain lives and voices on the page, they can be more aligned with the work itself than a funnel that demands instant mass appeal.

How readers can bend the graph

The usual story of publishing gives readers a passive role: books appear, readers choose from what exists. But in a system where a handful of companies pre‑select what “exists,” each reader’s choices matter more than they might seem.

If readers stay within the beam projected by the Big Five—front‑table displays, algorithmic “you might also like” carousels, films and series tie‑ins—then the graphs remain stable. Risk stays concentrated in precarious corners. Books like mine remain politely declined as “not viable.”

If readers step even slightly outside those thickest lines, the graphs begin to bend. Some ways to do that, especially in places like Australia:

Visit independent bookstores and ask specifically for small‑press titles or books from local micro‑publishers like Giramondo, Transit Lounge, or Affirm Press, which have repeatedly produced prize‑winning work despite limited marketing budgets.[11]

Follow literary prizes and longlists rather than bestseller charts; the Stella, Miles Franklin, and Prime Minister’s Awards have collectively showcased small‑press books at rates far exceeding their market share.[11]

Buy directly from independent publishers’ websites or from authors’ own shops and crowdfunding campaigns, where a single sale can mean significantly more revenue than a remaindered chain‑store copy.[11]

Treat word of mouth as a political act: when a book from outside the towers speaks to you, talk about it, lend it, post about it, make it part of your own informal “marketing department.”

None of this dethrones the skyscrapers overnight. But each action slightly redistributes attention, money, and cultural capital. Each action tells the people who run the spreadsheets that there is, in fact, a market for something else.

The thin, stubborn line

So yes, my book bounced off their doors. Yes, the charts say the Big Five own the centre of the map, with their billions in revenue and their near‑monopoly on bestseller lists. But the edges of those charts are alive. In that messy, under‑lit territory—small presses, self‑published experiments, translated oddities, regional houses—other maps are being drawn all the time.[2]

If you, as a reader, step outside the thickest lines—if you pick up the small‑press book, the translated novel from a country you have never visited, the self‑published thing your friend won’t shut up about—you are bending the graph, even if only a little.[10]

And maybe that is where this story belongs. Not as another neatly slotted product in one of five skyscrapers, but as a thin, stubborn line climbing up the side of someone else’s chart, insisting that literature is bigger than what five companies planned for us this quarter.

References

Publishers Weekly. (n.d.). They Don’t Call Them the Big Five for Nothing. https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/bookselling/article/97059-they-don-t-call-them-the-big-five-for-nothing.html

Publishers Weekly. (n.d.). The World’s Largest Publishers 2025. https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/98865-the-world-s-largest-publishers-2025.html

Friedman, J. (n.d.). My Year-End Review of Most Notable Publishing Industry Developments. https://janefriedman.com/my-year-end-review-of-most-notable-publishing-industry-developments/

LibLime. (2025, August 14). The Top 5 Publishing Companies of 2025: Why Librarians Prefer These Industry Giants. https://liblime.com/2025/08/14/the-top-5-publishing-companies-of-2025-why-librarians-prefer-these-industry-giants/

Reddit - r/PubTips. (n.d.). AMA: Big Five Marketer. https://www.reddit.com/r/PubTips/comments/1nw96ti/ama_big_five_marketer_umssalt/

Scholarly Kitchen. (2025, August 20). 2025 Update: Quantifying Consolidation in the Scholarly Journals Market. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2025/08/20/2025-update-quantifying-consolidation-in-the-scholarly-journals-market/

Jericho Writers. (n.d.). Best Book Publishers 2025. https://jerichowriters.com/best-book-publishers-2025/

LinkedIn. (n.d.). Book Market Just Gave Publishers Wake-Up Call Most Missed. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/book-market-just-gave-publishers-wake-up-call-most-missed-jentetics-w3zif

Statista. (n.d.). Book Publishing. https://www.statista.com/topics/9280/book-publishing/

Featherstone, A. (n.d.). Book Publishing and Author Statistics 2025 Running Tally. https://annafeatherstone.com/book-publishing-and-author-statistics-2025-running-tally/

ArtsHub. (n.d.). The Remarkable Prize-Winning Rise of Our Small Publishers. https://www.artshub.com.au/news/features/the-remarkable-prize-winning-rise-of-our-small-publishers-255776-2359600/

Sourcebooks. (n.d.). Sourcebooks Cracks the Big Five. https://www.sourcebooks.com/co

No comments:

Post a Comment