The Psychology Behind Criminal Behavior: Through the Lens of A Clockwork Orange

Ever wonder when humans first started deliberately hurting each other? Not by accident, not in self-defense, but actual premeditated harm?

Stanley Kubrick wondered too. He is one of my favorite director. His 1971 film A Clockwork Orange start when Alex DeLarge staring directly at us, confronting us to understand him. He is a teenage sociopath who commits ultraviolence for pleasure. We have built this entire system around punishment - massive prisons, surveillance everywhere, police forces with military-grade equipment - yet crime keeps happening. Kubrick’s film asks: what if we’ve had it backwards this whole time?

There’s an ancient story most people know. Cain and Abel, two brothers. They both give offerings to God. God likes Abel’s better. Cain loses his mind and murders Abel. Simple story, right? But think deeper about what actually happened inside Cain’s head. He wasn’t just angry. Something formulated inside his skull. He experienced rejection while watching his brother get approval. His entire sense of worth collapsed. That comparison destroyed him from the inside.

Alex DeLarge experiences something similar, though inverted. He doesn’t feel rejected or he rejects everything. He thinks that society offers him nothing meaningful and that cause a dead-end school, working-class drudgery, adults who’ve given up. He is bored, brilliant, and drowning in a world without purpose. So he creates his own meaning through Beethoven and ultraviolence.

Cain’s problem was feeling worthless next to Abel. Alex’s problem is finding nothing in legitimate society worth valuing at all.

Brain scientists today will back this up. When you feel envious, your pain centers activate - literally the same regions that fire when you’re physically hurt. People who constantly compare themselves to others become measurably more aggressive. Getting humiliated is one of the best predictors of future violence we have. Shattered identity, no emotional tools to handle it, plus feeling cosmically screwed over - that mixture produces violence.

Watch what happens when Alex gets caught. Society doesn’t try to understand him. They don’t ask what broke, what’s missing, why a smart kid chooses destruction. They throw him in prison, humiliate him, strip away his name and replace it with a number. Then they offer him the Ludovico Technique - a “cure” that’s really just sophisticated torture. They condition him so violently that his body revolts at the mere thought of aggression. Problem solved, right?

Here’s something interesting though. God doesn’t execute Cain afterward. Instead there’s this mark for protection, but also permanent exile. Cain wanders forever, cut off from home and meaning. He lives with his deed while losing everything that matters. That’s consequence, not revenge. This ancient text grasped something we’re still figuring out: pure punishment without redemption just breeds more violence.

Kubrick understood this too. After the Ludovico Technique, Alex can’t commit violence anymore. Success! Except he also can’t defend himself when his former victims attack him. He can’t choose good freely - he’s just a wind-up toy programmed to be harmless. They didn’t reform him. They didn’t address why he became violent. They just broke him differently. And when society has no use for broken things, they discard them. Alex attempts suicide, not because he’s been reformed, but because existence without agency or dignity becomes unbearable.

Let’s shift to actual history. Archaeologists dig up violence everywhere - cracked skulls, mass burial sites, bodies dumped away from communities. This goes back tens of thousands of years. But violence and crime aren’t identical. Crime requires society first. You need laws, property, social structures that can be violated. Some prehistoric person killing a rival over hunting territory? Just violence. Crime only exists once you’ve got states and rules to break.

Real crime records first appear on Sumerian clay tablets around 3000 BCE. Not myths, just administrative documentation. Someone stole grain. Someone committed murder. Witness statements. Boring paperwork proving crime had become an official problem needing official solutions. By 2100 BCE there are formal legal codes listing crimes and consequences. and when it all started—writing it down meant crime was already widespread, right?

No matter how dehumanizing it is, In Alex’s dystopian Britain, we find that crime has become so widespread that society embraces any solution, the government seems doesn’t care about rehabilitation or understanding root causes. They need results for the next election. Sound familiar? Politicians tour the prison showcasing Alex like a trained animal. “Criminality cured!” they announce. I think the priest is the only person who objects, asking whether removing free will can be called a cure at all. Nobody listens to him. Results matter. Dignity doesn’t.

So why do people commit crimes? not now, nobody has simple answers unless they are selling something. They say biology plays a part - brain damage affects impulse control and I wonder certain hormones correlate with aggression, and certainly childhood trauma physically rewires neural pathways. But identical biology creates wildly different results depending on circumstances. Genetics might load the weapon, but environment decides if anyone fires it.

Psychology is massive here. Neglected kids, people experiencing constant humiliation, anyone lacking clear identity or purpose - these show up repeatedly in criminal profiles. Viktor Frankl observed concentration camp prisoners and noticed that losing life’s meaning made people dangerous. Those feeling invisible, experiencing existence as fundamentally unjust, unable to build coherent personal narratives - that’s the psychological groundwork for crime.

Alex shows us this psychology in action. His parents are checked out. His school is meaningless. The adults around him are either corrupt or pathetic. He’s intelligent enough to see through everything society offers and find it empty. Legitimate paths to significance seem like traps leading to soul-crushing mediocrity. So he builds an illegitimate path instead - becoming a leader through violence, finding transcendence through Beethoven, creating meaning through destruction. It’s twisted, but it’s his. He’s chosen it. That agency matters more to him than morality.

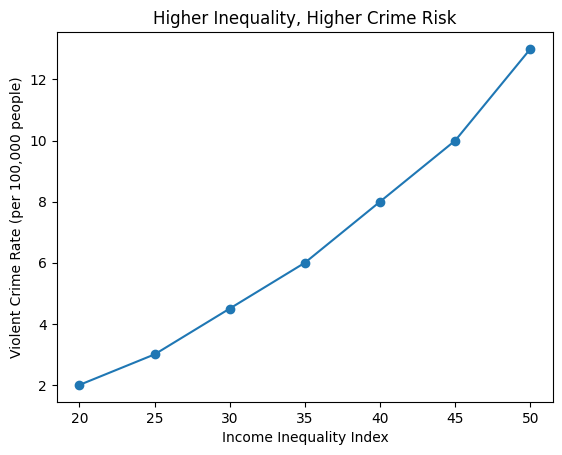

Social and economic factors might be biggest though. Modern researches shows clearly now: inequality drives crime more than poverty itself. Being poor doesn’t automatically make you criminal. Being poor while watching rich people display wealth you’ll never reach? That’s dangerous. Poor people in relatively equal societies commit far less crime than equally poor people in highly unequal ones. Block legitimate paths to dignity and status, people build illegitimate ones.

The film shows this repeatedly. Alex’s world is divided between the haves and have-nots. The rich live in modern homes with art on the walls. Alex and his droogs prowl crumbling neighborhoods. The wealthy writer Alexander lives in privilege, insulated from the violence festering in society’s lower levels. When that violence crashes through his door, he’s outraged - how dare they? The film suggests his comfortable life depends on Alex’s class staying suppressed. Inequality isn’t a bug. It’s the system working as designed.

Philosophers have circled this forever. Rousseau thought inequality corrupted natural human empathy. Nietzsche viewed crime as the drive for significance going destructive when positive outlets get blocked. Dostoevsky saw crime as revolt against meaninglessness. These aren’t just theories - they describe psychological realities researchers now measure.

Kubrick dramatizes all three. His protagonist (or antagonist) lacks empathy not because he is inhuman but because society taught him other humans exist only for his use or their opposition. Here I can compare his drive for significance - that Nietzschean will to power - has nowhere legitimate to go, so it explodes outward in violence like dancing star with chaos inside. And his crimes absolutely work as revolt against meaninglessness. When he says “What is it going to be then, eh?” he’s not just asking about tonight’s activities. He is asking what life means at all when society offers nothing worth having.

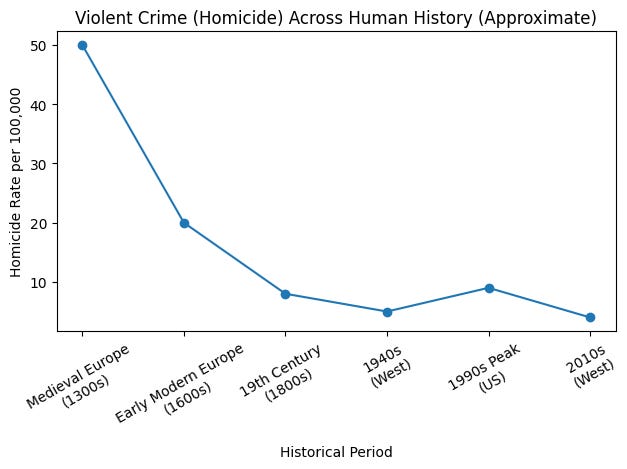

Some researcher or so called well-read romanticize the past, pointing to the 1940s or 1950s as proof of better times. Crime rates were lower then versus the violent decades that followed. But there’s a catch: World War II pulled millions of young men - the demographic most likely to offend - out of cities into military service. Fewer young men around meant less crime. Demographics, not morality.

When we Look at centuries instead of decades and something surprising appears. It shows us something real, violence in Western societies has dropped dramatically over time. Medieval European cities had murder rates hitting 40 to 110 per 100,000 people. Modern Western nations usually sit under 5 per 100,000. As governments monopolized violence, built legal systems, expanded education, created welfare programs - crime declined steadily.

But zero never happens. Even the safest nations record murders, assaults, robberies. The reason is fundamental. Crime emerges from human competition over resources, status battles, dignity struggles. Wherever inequality exists, wherever some hold power while others feel powerless, wherever meaning collapses and identities fracture - crime follows.

History’s solution was straightforward: make crime terrifying. Public executions, brutal beatings, harsh prisons. Scare people enough and they won’t offend. This failed completely. Pickpockets worked crowds watching public hangings in London. America locks up more people per capita than anywhere and still has significant crime. Often harsh punishment worsens things - over sixty percent of released prisoners get arrested again within three years.

The Ludovico Technique is Kubrick’s nightmarish extension of this logic. Make crime physically impossible through conditioning so brutal it destroys the person’s autonomy entirely. The film shows us exactly why this fails. Our hero, here, can’t be violent anymore, but he hasn’t changed inside. He is still the same person, just trapped in a body that rebels against his will. The moment the conditioning pull off down at the end, he is back to his old self, fantasizing about violence while politicians feed him and promise him power. Nothing was solved. The violence just got temporarily suppressed, and meanwhile Alex was tortured, humiliated, and nearly destroyed.

Why does punishment fail? Because crime usually isn’t rational calculation. People don’t spreadsheet costs versus benefits before offending. They act from rage, desperation, damaged identity, feeling wronged. Humiliating punishment often strengthens criminal identity rather than dissolving it. First-timers enter prison and learn to be better criminals. Strip dignity away and you create resentment. Resentment becomes defiance. Defiance leads back to crime.

Alex’s prison time doesn’t reform him - it just teaches him to manipulate the system better. He pretends to find religion because the chaplain has books and relative kindness. He volunteers for the Ludovico Technique not from remorse but from strategic calculation - it’s his fastest path out. The punishment system assumes he’ll emerge changed. Instead he emerges more cynical, better at deception, and eventually more broken. When his conditioning fails and society needs him for propaganda, they restore his violence and give him power. The system has completed its perverse circle.

What actually works then? Forget eliminating crime entirely - focus on substantially reducing it. Evidence clearly points several directions. Early childhood intervention shows strongest results. Babies forming secure caregiver attachments commit dramatically less crime lifelong. Quality early education reduces crime decades later. Addressing trauma before it hardens prevents violence from rooting. This isn’t sexy policy - spending money on toddlers who’ve done nothing wrong. But prevention starts before crime happens, in those first years when brains and relationships form.

Imagine if someone had reached Alex earlier. What if his intelligence had been channeled into something meaningful? What if his love of music had been nurtured instead of ignored? What if society had offered him legitimate paths to significance that matched his capabilities? The film never shows us this possibility because Kubrick wants us to see the failure of addressing crime only after it’s already happened. By the time we meet Alex, intervention opportunities have passed. Now society has only bad options: let him terrorize people or destroy his humanity. Both choices are failures.

Reducing inequality works across different societies. This isn’t ideology - it’s observation. Places with fair wages, accessible education, genuine social mobility have noticeably less violent crime. The mechanism is simple: people seeing real paths to dignity through legitimate means follow those paths. When legitimate paths seem permanently closed, some build illegitimate alternatives. American crime peaked in the 1980s and early 1990s exactly as inequality exploded.

Restorative justice revives ancient wisdom. Indigenous peoples - Maori in New Zealand, First Nations across Canada - traditionally emphasized accountability, repair, reintegration over pure punishment. Scandinavian nations adapted these principles with remarkable results. Norway’s reoffending rates rank globally lowest. The process makes offenders face victims, understand harm caused, make amends where possible, rebuild community connections. Crime drops because identity gets rebuilt instead of destroyed.

A Clockwork Orange shows us the opposite. Alex never meaningfully confronts his victims. The writer Alexander becomes an instrument of political revenge, not a person seeking genuine accountability. When Alex encounters his former droogs - now police officers - they use their power to beat him nearly to death. Everyone wants vengeance. Nobody wants restoration. This cycle continues endlessly, whatever we do: violence breeding violence, humiliation breeding rage, and power shifting hands while the underlying sickness goes untreated.

Meaning, belonging, work matter enormously. People feeling useful and seen commit fewer crimes. That’s statistical fact, not sentiment. Unemployed men lacking dignity or purpose consistently form the most dangerous demographic. The Great Depression created mass unemployment without support and crime rose. World War II created full employment and crime fell. Programs offering meaningful work, skills training, genuine community connection cut reoffending far more than lengthy sentences.

The film’s most damning detail might be its setting: a society so sterile, so empty of authentic meaning, that even “normal” people seem half-dead. Alex’s parents watch television numbly. His post-corrective officer does his job with bureaucratic indifference. The writer obsesses over his political revenge. The government cares only about power. Where in this world would a reformed Alex find meaning? What community would embrace him? What work would give him dignity? The film suggests that even if Alex wanted to change, society offers him nowhere legitimate to go.

That first crime - Cain killing Abel - wasn’t about survival or theft. It was comparison without compassion, identity shattering, rage from feeling unseen by both God and humanity. Every crime since echoes that original wound somehow. Crime won’t disappear because people aren’t perfect. We compete, compare, envy, rage. We build hierarchies creating winners and losers. We construct societies distributing dignity unequally. Crime flows from these realities as naturally as water flows downhill.

Alex DeLarge is an extreme case - a charismatic sociopath who revels in cruelty. Most criminals aren’t like him. But Kubrick uses Alex to expose truths about how we respond to crime.

We prefer simple solutions: lock them up, condition them, break them if necessary. We avoid asking harder questions about what our society produces and why. We punish individuals while maintaining systems that predictably generate more criminals. We break people and call it justice.

Crime can drop dramatically though. Not through harsher sentences - that experiment ran for millennia and failed. Not through more cameras - surveillance records crime but doesn’t prevent the psychological fractures producing it. Not through behavioral conditioning that strips humanity while leaving root causes untouched. Crime declines when we stop asking “how do we punish” and start asking “what broke this person.” Answers typically involve childhood trauma, chronic humiliation, blocked dignity paths, collapsed meaning, social exclusion. These are solvable problems. We know how to prevent childhood trauma, build more equal societies, offer meaningful work, restore people instead of just punishing them.

What’s missing isn’t knowledge - it’s willingness. We prefer emotionally satisfying narratives of good versus evil, monsters needing cages, punishment equaling justice. Real work is messier. Investing in other people’s children. Reducing inequality benefiting us. Treating offenders with dignity they haven’t earned but desperately need.

The film ends ambiguously. Alex is “cured” of his cure, back to his violent self, now embraced by the same government that tortured him. Politicians feed him steak and promise him a job. Photographers snap pictures. Everyone’s smiling. Nothing has changed except who holds power and who owes favors to whom. Kubrick leaves us with this poison: a system that creates criminals, punishes them brutally, fails to reform them, then occasionally recycles them for political advantage. Round and round it goes.

The deepest lesson from that first crime might be God’s initial question:

not “what did you do” but “where is your brother.”

Asking about relationship, about mutual responsibility. Cain’s response - “am I my brother’s keeper” - stands as history’s first social responsibility dodge.

That question remains unanswered. Are we responsible for each other? Are we responsible for the Alexes of the world - the ones bored and brilliant and drowning in meaninglessness? Are we responsible for building societies that offer genuine dignity to everyone, not just elites? Until we say yes through actual policy and genuine commitment to reducing conditions that fracture people and breed violence, we’ll keep experiencing crime’s consequences while refusing to address its causes.

Violence springs from shattered meaning. The only response actually working is repairing that meaning, look after one child, look after one community, and look after one intervention at a time. That would work. A Clockwork Orange shows us what happens when we choose punishment over understanding, control over dignity, political expedience over genuine reform. Kubrick made this film over fifty years ago. are we not still trapped in the same cycle, still asking the same questions, still choosing the same failed solutions?

The ultraviolence continues. And we continue wondering why.

Note: First review 23 Nov 2024 Updated: 1/17/2026

Image: IMBD

No comments:

Post a Comment